) at the end of the movement.

) at the end of the movement.The harmonic pedal comprises twenty-nine chords,

Note: The original paper included a great many musical examples. Copyright restrictions make it difficult or impossible to access the score to the Quartet on the internet. I have elected, at least for the time being, to omit musical examples here rather than engage in the time-consuming process of rescanning large portions of the score. (It is hoped that the text alone will still be somewhat informative!)

Example here (omitted)

The pattern occurs nine times in full, plus values 1 – 15 of a tenth occurrence, with 14 and 15 tied (making the value  ) at the end of the movement.

) at the end of the movement.

The harmonic pedal comprises twenty-nine chords,

Example here (omitted)

played on the values of the rhythmic pedal. Thus, at the beginning of the piano part, chords 1 – 17 fall on values 1 – 17 of the rhythmic pedal, and chords 18 – 29 fall on rhythmic values 1 – 12 as the rhythmic pedal begins its second run-through; then chords 1 – 5 on values 13 – 17; chords 6 – 22 on values 1 – 17; and so on to the end. The harmonic pedal is played in its entirety five times; chords 1 – 22 of a sixth use of the pedal are played. However, by design or by error (the latter is suspected), chord 3 was left out of the fourth occurrence of the harmonic pedal (at one before E in the score).

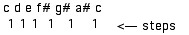

The cello part, meanwhile, uses quite another rhythmic pedal, as well as its own melodic pedal (analogous to a harmonic pedal, but using single pitches instead of chords). The rhythmic pedal of the cello, fifteen values long, is

Example .

The cello's rhythmic pedal happens seven times, plus values 1 – 4 of an eighth. Once again, Messiaen seems to have made a mistake, for in the sixth occurrence of the pedal, value 5, which should be an eighth note, is a quarter! (In the score, see the last note of the second bar of F.)

The cello's melodic pedal is

Example .

Only five notes long, this pedal occurs twenty-one times, with pitches 1 – 4 of a twenty-second time.

All of these pedals shall now be examined in more detail. As for the rhythmic pedals, the strange, uneven rhythms are derived from Hindu rhythmics (decî-tâlas). Some of the rhythms used here are the râgavardhana (example), the candrakala, and the laksmisa. The germ of the râgavardhana rhythm — example — contains an example of another favorite Messiaen device, the added value. An added value is a usually short "extra" rhythmic value added to a simple constant rhythm; the added value may be either tied to another note or articulated. Thus, added values might alter the pattern  in any of the following ways (as well as others):

in any of the following ways (as well as others):

Four examples .

(Added values figure much more prominently in the sixth movement of this work than they do here.)

The cello's rhythmic pedal exemplifies yet another device that is practically exclusively Messiaen's: the non-retrogradable rhythm. A non-retrogradable rhythm is one that is the same backwards as forward. The rhythmic pedal in the cello consists of two such rhythms:

Example .

The cello's melodic pedal consists of artificial harmonics. They are played by stopping the string at the point of the lower printed note (oval note-head), simultaneously lightly touching the string a perfect fourth higher (diamond note-head), at which point is a node. This allows the string to vibrate in four parts, yielding a pitch two octaves above the stopped note:

Example .

The pitches in the cello part, c - e - d - f# - Bb, contain all but one of the pitches of, and thus strongly suggest, a whole-tone scale. The whole-tone scale, furthermore, is the first of Messiaen's own seven modes of limited transposition. The modes of limited transposition are so named because, unlike ordinary scales and modes, a mode of limited transposition (hereafter called simply a mode) can be transposed only a few times (in any case, by a maximum of some interval less than an octave) before the original scale recurs. In the whole-tone scale (the first mode), one can start with the original, or first transposition

(the first transposition of each mode begins on c), and transpose it up by a half step to get a new set of pitches:

c# d# f g a b c#

which make up the second transposition of the first mode. But the "third transposition":

d e f# g# a# c d

is identical to the first, so there actually is no third transposition of the first mode. Messiaen finds the first mode tolerable only when "mixed with harmonic combinations . . . foreign to it." The chords of the piano's harmonic pedal certainly fulfill that requirement.

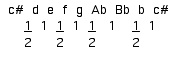

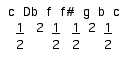

Now examine that harmonic pedal. Chords 23 – 28 are written in the second mode, second transposition:

The second mode is often called "the" octatonic scale: alternating whole and half steps. It can be realized in any of three transpositions. The second mode was used occasionally by earlier composers, most notably Scriabin.

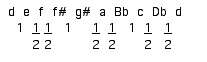

Chords 16 – 21 of the harmonic pedal contain the notes

and are thus in the third mode, third transposition. (Four transpositions of the third mode are possible.)

Chords 1 – 8 of the harmonic examples of one of the components of Messiaen's harmony that he most frequently uses: the chord on the dominant:

Example .

This chord contains all the notes of the major scale and supposedly resolves as shown:

Example .

Messiaen chooses almost without fail to precede the chord on the dominant by appoggiaturas as shown:

Example .

Chords 1 – 2 of the harmonic pedal, as can be seen, are exactly that: a chord on the dominant preceded by appoggiaturas. (Messiaen calls the effect of this combination a "stained-glass-window" effect.) Chords 3 – 8 involve various inversions of the chord.

The clarinet part in the first movement has the indication comme un oiseau (like a bird). Messiaen is himself an accomplished ornithologist and is fond of incorporating bird song into his work. Here the song of the blackbird is used. According to Messiaen, the blackbird song is characterized by climacus resupinus (reversed ascent). The clarinet line is the principal melodic line in this movement.

The violin supplies what Messiaen calls "secondary counterpoint," which sounds quite bird-like as well. The entire range of the violin part in the first movement falls into the higher tessitura of the instrument:

Example .

The only notes used are

As shown, this "scale" divides the octave into equal halves (c# – g, g – c#), one of which is divided completely into half steps, the other of which is divided into whole steps.

II. Vocalise, pour L'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (Vocalise, for the Angel Who Announces the End of Time)

The second movement is in the form ABA', but the middle section is in a way closely related to the outer ones. The A section, marked Robuste, is loud, driving, and, particularly in the piano, full of accents. The clarinet run in m. 2,

Example ,

is an instance of arpeggiation of the chord on the dominant with appoggiaturas. Another occurrence of the chord on the dominant with appoggiaturas takes place in m. 8; this time it is arpeggiated by the clarinet and then played in block fashion by the piano, without appoggiaturas, but with an added note (the (c#):

Example .

Note that the clarinet part includes gestures identical to those found in the violin part in the first movement:

Two examples.

In m. 1 are chords embodying a new concept: resonance. A chord may be enhanced by playing some of its natural overtones (superior resonance) or undertones (inferior resonance).

Example .

On beat 3, the two bass notes create inferior resonance. Inferior resonance is used in the piano part for a number of bars at the beginning of the movement.

At C, note that the violin and cello run is in the third mode:

Example .

The middle section, at D, is in extreme contrast to the opening. It is slow, almost eerie. The strings are muted. The piano plays what Messiaen terms "cascades of blue-orange chords." The clarinet does not play during this section.

However, note that the pitches the strings play from D to E are identical to the pitches they played at the beginning of the movement!

Two examples .

Despite this fact, the sections seem on hearing to bear no resemblance, because of the drastic changes in tempo, rhythm, and general mood.

As for the "blue-orange chords" in the piano, they introduce still more gems of Messiaen's harmony. Looking first at the second measure of D,

Example ,

we find "superposed fourths": a perfect fourth in the left hand, and another in the right. Moving now to two before F, a new special chord is introduced:

Example .

Messiaen calls this the chord in fourths; it is created by stacking a succession of six notes a fourth apart, alternately augmented and perfect. The chord in fourths contains all notes of the fifth mode (a mode with six transpositions):

The third and fourth measures of D

Example

contain examples of still another chord from the Messiaen harmonic repertoire — the chord of resonance. Messiaen says that the chord of resonance, in its root position, built on c as shown:

Example

contains "nearly all the notes perceptible, to an extremely fine ear, in the resonance of a low c..., tempered." Messiaen's method of inverting this chord is unusual. Here is the chord and its first and second inversions:

Example .

The method of inversion is the following:

1) In right hand only, put bottom tone on top.

2) Transpose right-hand cluster down so that bottom note is the same as before.

3) Repeat 1) and 2) with the left-hand notes only.

Note that the chord of resonance and its second inversion contain between them all the notes of the third mode.

The final (A') section is a condensation of the A section. Note the downward run of the strings, in the third mode:

Example

a reversal of their upward run in the A section.

III. Abîme des oiseaux (Abyss of the Birds)

As the title suggests, this third movement, for clarinet solo, is full of bird song: first sad, then joyous, then sad again (ABA').

Messiaen explains that the contour of the passage in m. 11 is taken from Grieg's "Chanson de Solveig" from Peer Gynt:

Two examples .

At the Presque vif, the blackbird breaks into a happy song, similar to his song in the first two movements:

Four examples .

Later, the bird sings an arpeggiated chord on the dominant with appoggiaturas:

Example .

When the sad song returns, it is an octave lower, in the clarinet's chalumeau register:

Two examples .

This movement is noteworthy for its dynamic range, most graphically illustrated here:

Example .

IV. Intermède (Interlude)

Although most (not all) of Messiaen's music is in a meter, the sense of meter generally tends to be lost as he freely spins out his celestial harmonies and bird-like melodies. Such is not the case in the fourth movement. The movement, which uses only the violin, clarinet, and cello, is in a straightforward 2/4; it is lighter in character than any of the other movements.

The opening theme, stated in unison by the three instruments, is in the second mode:

Example .

In the eleventh bar, the instruments remain in rhythmic unison, but break into tertian harmony.

Example

There is arpeggiation of the chord on the dominant with appoggiaturas in the clarinet at various points in the movement. In the three bars preceding H, the chord on the dominant with appoggiaturas is played successively in first inversion, fifth inversion, and root position:

Example .

At C, the clarinet part is very similar to a segment from the second movement:

Two examples .

This pattern occurs several more times in the fourth movement, including the ending. At F, a new theme is presented, more flowing and metrically less square than the theme of the opening:

Example .

The first four bars are presented by the strings; the next five by the clarinet.

The first theme returns to close the movement.

V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus (Praise to the Eternity of Jesus)

This extremely slow and lyric movement for cello and piano is an example of a song-sentence. Messiaen explains: "The song-sentence is divided thus: a) theme (antecedent and consequent); b) middle period, inflected toward the dominant; c) final period, an issue of the theme."

Here, the first six measures of the cello part are the theme's antecedent:

Example

the following six its consequent:

Example .

Note that the theme, up to the last two measures, is in the second mode. However, E major is strongly felt for several reasons: the theme begins on b, the dominant, and descends to a point of arrival on e in m. 3; the piano part begins in m. 3 with an E-major chord and ends with another in m. 6, while the cello is holding a b (the dominant). In the next six measures, the music begins moving away from e as a tonic.

At B, the middle part begins. It falls into three subperiods — the first six bars:

Example ,

the next four:

Example ,

and the following four.

Example .

The middle section builds to a terrific climax at D, at which point "the bottom drops out:" the return of the theme takes place over a subito ppp dynamic indication. The theme is restated in pianissimo, again in antecedent-consequent form, bringing the movement to an appropriately heavenly close in E major.

VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes (Dance of Fury, for the Seven Trumpets)

The sixth movement features the four instruments playing strictly in unison throughout. Its mood is powerful and driving.

The theme at the beginning is melodically and rhythmically jagged. The continual stabs and delays are the result of a device mentioned earlier in passing: the added value. Here are a few bars with the added values marked:

Example .

Here are the same bars with those notes removed:

Example .

Note how the sense of drive is almost totally dependent on the presence of these irregular interjections. Incidentally, the theme here was foreshadowed in the fourth movement:

Example .

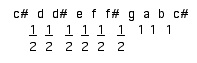

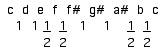

Messiaen, in a discussion of added values in his book, quotes the entire first portion of the movement (up to F), and labels it "an example written entirely in the sixth mode of limited transpositions." Here is the sixth mode (first transposition:

.

.

(Six transpositions are possible.) A little examination shows him to be in error. As a matter of fact, the modes used in the portion up to F are the following (see the example on p. 22):

mm. 1 – 4: mode 6

mm. 5 – 6: mode 2

mm. 7 – 8: mode 6

mm. 9 – 10: mode 2

m. 11: (chromatic)

mm. 12 – 13: (chromatic except d-natural)

mm. 14 – 17: mode 6

mm. 18 – 19: mode 2

mm. 20 – 21: mode 6

mm. 22 – 23: mode 2

mm. 24 – 25: (chromatic)

Messiaen mentions that in this section he uses "...some Greek [syllabic] feet: 2nd paeon [.-..], 2nd epitrite [-.---], amphimacer [-.-], antibacchius [--.]."

The section at F uses two devices mentioned earlier: a melodic pedal and non-retrogradable rhythms. The melodic pedal is made up of these sixteen pitches:

Example .

Each of the first fourteen measures in this section is made up of one non-retrogradable rhythm. The second seven measures are rhythmically identical to the first seven, respectively.

Example .

Here are the non-retrogradable rhythms making up the first fourteen measures of F:

Fourteen examples .

At I, there is an alternation between two figures at intervals of two to three bars:

Example .

1) The melody of the opening theme of the movement, but fragmented and predominantly in constant sixteenth notes, played by the violin, cello, and piano;

2) the notes f – c# – a, played loudly and repeatedly in the time ratio 2 : 1 : 2 by the clarinet and piano with the overall pattern rhythmically augmented and diminished to various degrees. At first, the f – c# – a pattern is played within the space of an octave, but the last two times, the notes are displaced to different octaves:

Example .

At L, material from the beginning is presented in constant sixteenths:

Example .

At M, a fragment of the opening theme is varied rhythmically:

Example .

A wild driving section ensues, climaxed by a run in the second mode:

Example .

After a great crescendo on a trill, the opening theme is presented, rhythmically altered, in extreme fortissimo, using octave displacement on each successive note, so that it is not easily recognizable:

Example .

The movement closes with short segments recalling some of its various sections.

VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (Cluster of Rainbows, for the Angel Who Announces the End of Time)

The seventh movement is an exploration of two themes by development. The first theme, a slow and lyric melody in the second mode, is stated by the cello at the beginning, and is supported by soft, pulsing chords in the piano:

Example .

The second theme, beginning at B, is borrowed directly from the opening of the second movement in the piano part:

Two examples .

The other instruments enhance the theme with staccato notes. In the fifth measure of the second theme, the violin and clarinet play the theme of the sixth movement in staccato sixteenths:

Two examples .

At the same time, the piano takes a fragment of five notes

Example

and develops it:

Example .

The fragment is first played in inversion, then normal motion, then interversion (rearrangement of notes), then an interpolated Db, then retrograde (with an extra Db), and then interversion (with an extra Db). The first ten notes, incidentally, contain all the notes of the fifth mode.

At D the first theme returns, played by the violin, but the clarinet adds a countermelody this time:

Example .

The second theme returns at E. This time, Messiaen exploits four rhythms for quite a few bars. The rhythms are the following:

Four examples .

Meanwhile, the piano is playing chords borrowed from the second movement:

Two examples .

A few bars later, the same chords are played in retrograde by the violin, clarinet, and cello, while the piano is playing a chord on the dominant with appoggiaturas with inferior resonance:

Example .

After G the clarinet plays the first theme with a col legno (played with the wood of the bow) cello accompaniment, while the violin plays "arabesques":

Example .

At B the piano plays the development of the five-note fragment as it did earlier, the clarinet plays the theme of the sixth movement in constant sixteenths, the violin plays parallel diminished fifths on a rhythmic fragment from the first theme of the present movement, and the cello plays a pizzicato countermelody:

Example .

In the third bar of I, the piano plays a stream of chords while the other instruments play it in retrograde:

Example .

At J comes what Messiaen calls "the jumble." While the clarinet is arpeggiating the chord on the dominant with appoggiaturas, the violin and cello are playing the first theme in equal doubled sixteenths, and the piano is playing chords from the second theme:

Example .

This section broadens and builds to a final variation of the first theme played by the violin, clarinet, and cello in the high register, with the strings trilling throughout, while the piano arpeggiates a series of chords:

Example .

There is a short recall of the second theme, and then with a downward tumble of chords in the piano, this remarkably complex movement comes to a close:

Example .

VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus (Praise to the Immortality of Jesus)

The eighth movement is a beautiful slow movement for violin and piano.

This movement is an example of a binary sentence. A binary sentence consists of the following sections:

1) a theme

2) a modulatory commentary, inflected toward the dominant

3) the theme

4) another commentary, which returns to the original key.

Here the section from A to B is the theme:

Example .

The tonic is clearly e. The scale used sounds modal; it features a raised fourth and lowered seventh. The five-note fragment from the second theme of the seventh movement appears in this theme:

Example .

The commentary on this theme

Example

is built from this fragment:

Example .

The modulation is accomplished by way of an ascending series of triplets in the second mode.

The return of the theme is exact. The second commentary begins just as the first, but the ascending triplets commence a minor third lower the second time.

Example

Gradually, the violin line ascends to the highest note in the piece, and the music dies away to extreme pianissimo, into Heaven and eternity.

Messiaen has created a complete theory of music and has fashioned from it a work of marvelous invention and, above all, rare beauty. Such can only have been the work of genius.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Messiaen, Olivier. Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps. Paris: Editions Durand & Cie, 1941.

–––––, trans. John Satterfield. The Technique of My Musical Language, vols. 1 and 2. Paris: Alphonse Leduc, 1956.

–––––. Program notes for his Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps. Music Guild MS 150.

–––––. Program notes for his Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps. RCA Red Seal ARL1-1567.